Poker isn't exactly your run of the mill job or hobby. It's quite unlike most of the other activities that we choose to participate in. Our level of control in poker is very small and our ability to accurately evaluate it - very limited. The reason for that is twofold. First of all, the best poker players in the world have a relatively small advantage over amateurs when compared to other sports.

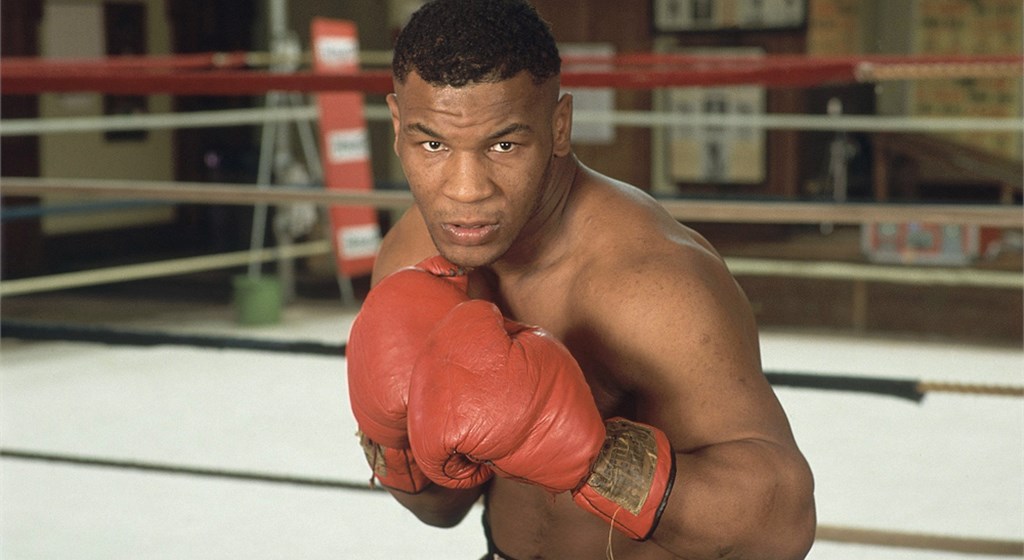

If you set-up the stacks low enough and the blinds fast enough even Phil Ivey can't guarantee that he's going to beat Joe Schmoe ten times out of ten in a head's up match. Meanwhile, no matter how big or small you make the ring or the boxing gloves, Mike Tyson will beat the same Joe Schmoe without breaking a sweat one hundred times out of one hundred. Second of all, there's variance. Luck factor in poker is so huge that an amateur beating a pro in a short series of a few hyper turbo heads up matches wouldn't be that shocking when compared to a guy of the street knocking out Mike Tyson.

Poker players are therefore in a constant state of doubt when it comes to their level of ability. It seems like no matter what we do, variance always has the last word - and that's a dangerous realization. Poker outcomes are rarely in line with the amount of effort we invest in the game and that can lead players to experience a phenomenon called "learned helplessness". Learned helplessness is a reason why many poker players fail and in this article, we're going to shed more light on this issue.

Dogs, Elephants and Poker Players Have it Rough

Have you ever wondered how circus workers are able to control the living tank of an animal that's an elephant? It's all a matter of proper long-term conditioning. The owners chain young elephant to a post that's sturdy enough to withstand the escape attempts of a small animal and after a large number of those attempts the elephant simply accepts his faith. The animal learns that it's in a helpless situation and the power of this realization is so strong and persistent that even when the elephant grows thousands of pounds larger, it doesn't attempt to change its faith.

With that powerful anecdote out of the way, let's talk some science, particularly the research on classical conditioning (the process by which an animal or human associates one thing with another) that was conducted in the 1960's by Martin Seligman and his colleagues. Scientists played a rather cruel riff on the Pavlov's dog idea by subjecting canines to electric shocks that were previously telegraphed by a sound cue. Some dogs were placed in the environment where they could prevent the shock from happening by pressing a button after they've heard the sound, while the rest of the poor test subjects were denied that option.

The first group quickly learned the significance of the sound cue and the button press in order to stop the shocks before they happened. The second group eventually stopped fighting and just like the Pavlov's dog before them, reacted to the sound cue with whimpering before the shock even happened. In the second part of the experiment, dogs were placed in a box divided by a small fence where one half of the floor was rigged to give subjects electric shocks and the other half was perfectly safe.

Here's where the scientists made their profound discovery. While dogs that were previously given the option to prevent the shocks by pressing a button, quickly learned a new way of saving themselves from a bad outcome by jumping over the fence, the second group of dogs learned that they were helpless in the face of the dreaded sound cue followed by a shock and instead of trying to jump the fence in this new environment, they were lying down in resignation as soon as they heard the first sound cue. Poor dogs learned to be helpless.

What does it all have to do with poker? Further studies proved that learned helplessness isn't exclusive to the animal kingdom.

Learned Helplessness, Variance, and Learned Optimism

The existence of a poker player in the middle of a soul-crushing downswing isn't all that different from the fate of one of those poor dogs in the previously mentioned experiment. A constant stream of bad beats that seems to be unaffected by our actions is like a series of electric shocks without a button that can disable them. Even a very good 5bb/100 player can experience downswings and breakeven stretches that can be counted in hundreds of thousands of hands, so the problem of learned helplessness can potentially affect all of us.

Humans have a natural tendency to assign causes to our actions and the effects of said actions. Attribution is the process by which individuals explain those causes. If a poker player always attributes his poor results to this external, stable and global force called variance that he can do nothing about, he'll quickly learn to be helpless which will, in turn, cause him to stall or even quit the game altogether, even when he's actually a winning player! On the other hand, if a player ignores the issue of variance and focuses on the factors that he has control over - like increasing win rate by way of poker education - he can avoid the trap of learned helplessness and thrive despite variance.

The key to counteracting the effects of learned helplessness lies in assuming a so-called internal locus of control. In personality psychology, a locus of control is the degree to which you believe that you have control over the outcomes of your actions. People with the internal locus of control believe that they are the masters of their own fate while the ones with the external locus of control believe that it's essentially all down to the luck of the draw. Here's the thing, variance is huge and it's real and we can't do much about it.

What we have control over is our own thoughts and beliefs about what it takes to be successful at poker. A poker player can become immune to the learned helplessness phenomena by ignoring what he or she can't control and focusing on becoming a better player. The existence of learned helplessness simply makes this choice even more crucial. It all comes down to a bit of a good old-fashioned self-confidence.